|

In 1908, Beano Bengaze's great grandmother, Beanette, opened the first hairdressing salon on the Navajo Reservation. It was a curious business decision. For one thing, the concept of cosmetically preparing one's hair just for the sake of glamour was foreign to most Navajos, and few were keen to indulge in it. For another, the Bengaze clan was venerated for its long line of shamans that stretched all the way back to the very genesis of humanity in the great cavern by the river Ood-nan-tunk. To ignore this heritage in favor of a frivolous career of the white man's culture was shameful, indeed. (Beanette, however, countered that her work was an adjunct to many shamanic rituals; she merely dispensed with their ceremonial aspects. The cutting of hair, for example, was often used to treat sick people. Medicine men believed that diseases entered the body through split ends. By trimming off these unhealthy follicles, then shampooing the hair with restorative agents, such as balsam, protein and corn pollen, the person would be returned to good health. Similarly, the application of henna or other coloring agents to the hair had for millennia been used as a form of magical protection. It was known that tinting the hair with dyes rendered the wearer invisible to adversarial spirit gods, plus it sometimes had the ancillary benefit of healing bunions.) But perhaps the decision that rendered the business most likely to fail was that Beanette located the salon in Teec Nos Pos, a tiny Arizona hamlet near the Four Corners area that in the early 1900s was smack in the proverbial middle of nowhere.

So why was it such a huge success? Two words: Mother Bumpkins.

Mother Bumpkins was a missionary from the Church of Ladders, an apocalyptically evangelical sect with corporate headquarters in Windsor, Vermont. Its followers, though few in number, were zealously allegiant. They spoke in noses rather than tongues, indulged in primitive electroshock massages in lieu of communion, and augmented scripture reading with extensive hallucinogenic therapy, but otherwise were similar to many other gospel-driven religions of the day. The church's name derives from a passage in the ninth chapter of the Book of Jehoshaphat: "One day, the Lord becameth holy annoyed at His malcontent children, and didst He then smite the Earth most annihilatively, causing widespread apocalypse and stuff; but lo, in a distant land didst a canny few climb out of the flaming abyss upon ladders; beseechest they then to the Lord for succor, and the Lord, in His leniency, didst bless them and give them sheep. Selah di da." (Paraphrased from the King Fisher Version.)

Church of Ladders members were very good at proselytizing, but Mother Bumpkins was the best. She peddled her religion as easily as if she were handing out free money. She even briefly counted Pope Pius X among her converts. (Historical note: When X reverted to his Catholic habit in 1907, he issued a Condemnation of Modernism encyclical, which denounced the Church of Ladder's teachings as blasphemous and heretical. You can look it up.)

In 1908, the church sent Mother Bumpkins to proselytize throughout the Navajo Nation, all 16¼ million acres of it. From Dinnebito to Dinnehotso, Sweetwater to Mexican Water, Rough Rock to Round Rock, the Diné eagerly embraced ladders. Billie Mae, Wampum Joe, Betty Sue, Fairlane Ford, Bunyip Boy, Talking God and all of the other animistic spirit gods that so infused Navajo culture summarily went the way of the Arizona penguin.

When Mother Bumpkins arrived at Beanette Bengaze's salon sometime later, however, she finally met her match. Because the hairdresser didnít immediately respond to her sales pitch, Mother Bumpkins decided to humor her by consenting to a haircut. She had to admit that her 'do did resemble Medusa's serpentine locks.

The ergonomically cozy salon chair put her at ease, Beanette's soothingly soporific snippings put her to sleep, and the balsam, protein and corn pollen rinse put her into a receptive frame of mind. Not adverse to employing her innate shamanic skills, Beanette gently talked about the benefits of a nice cream rinse, or perm, or dipilatory. Later, Mother Bumpkins awoke, refreshed and with fashionably fetching hair, and with a new purpose in life. Ladders, schmadders, she declared--who needed 'em? They were nothing more than runs in stockings, after all. On the other hand, a decent haircut was good for the human soul, got rid of bloodsucking parasites that called the scalp home, and was available at competitive prices at Beanette Bengaze's Hair Salon in Teec Nos Pos. This was the new message that Mother Bumpkins enthusiastically delivered on her proselytizing pilgrimage through the Navajo Nation. Soon, traffic to the salon increased so much that Beanette had to install a second chair, and then a third, and hire an assistant and a manicurist. Eventually she sold the operation to, of all people, Pope Pius X, and, to her family's relief, retired to a life of quiet shamanism.

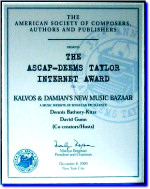

And what then of Mother Bumpkins? So convoluted is that story that it's best left for a time other than this 376th episode of Kalvos & Damian's New Music Bazaar, itself a study in convolution and bunions, apocalypse and henna, ladders and Kalvos.

|